Along with their brown sparrow relatives, some mostly gray birds regularly visit bird feeders. Although they do occasionally eat at trays, more often they are to be seen with doves and other birds feeding on the ground under the feeders. These birds are dark-eyed juncos and the subspecies that occurs here almost exclusively is the slate-colored junco. Local checklists record them by that subspecies name. They aren’t completely gray plumaged; their belly is white and, when they fly, they flash white outer tail feathers. If you look at them more closely, you’ll also see that their bill is slightly pinkish as are their legs.

Most birders welcome these juncos to their feeding stations simply because they represent an additional visitor. But they don’t have the charisma of many of the other birds. Their neutral coloration doesn’t have the flash of the cardinal or oriole. They don’t dash about like chickadees or head down trees like nuthatches. They aren’t tiny like kinglets or feisty like those hummingbirds that chased each other away from your sugar-water tubes all summer.

Click here to become a member!

Click here to donate!

Birders think of juncos as wintering species here even though a few do remain to breed, mostly in the higher elevations of the Southern Tier. In fact, they are often called snowbirds, a name shared with the entirely different appearing snow buntings. I get great pleasure watching a group of juncos, often together with a few tree sparrows, popping up from a snowdrift individually like untimed pistons to pick seeds from winter weeds.

Several years ago, I spent a week in the West where I came across another subspecies of the dark-eyed junco called the Oregon junco. When I first saw the bird, I almost mistook it for a towhee as it had a black hood. It turns out that this and other junco subspecies occasionally appear here on the Niagara Frontier as well. Not much attention is paid to them, however, as birders — and those who keep species lists in particular — don’t “count” subspecies.

A species is defined as a group of individuals capable of interbreeding and producing fertile offspring. A subspecies is a group within a species with differing characteristics like those black hoods or in their genetic make-up, but that can interbreed with other subspecies. That they do not do so is usually due to the fact that those subspecies do not occur in the same region. Indeed, these little juncos who visit your feeders have been serving for about a hundred years as a perfect model for studying subspecies differences and their evolution. And you have a wonderful opportunity to learn about that history. Indiana University’s Center for the Integrated Study of Animal Behavior has produced with National Science Foundation support an hour and a half of film titled Ordinary Extraordinary Junco to which you can gain access at juncoproject.org.

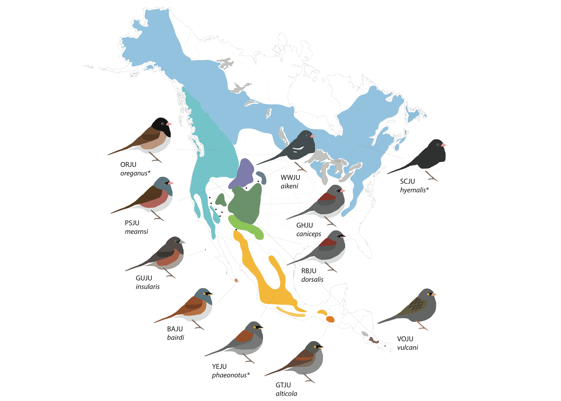

The film follows the activities of an international team of scientists as they study these birds. They extend the work of Alden Miller, who spent the 1930s collecting 11,774 juncos across North and Central America to determine their differences. He identified 21 distinct groups, 15 in the United States and Canada. Since Miller’s time those United States groups have been reduced to the six subspecies of the dark-eyed junco. Additional subspecies south of the U.S.-Mexico border belong to another junco species: the appropriately named yellow-eyed junco.

I encourage everyone to watch at least the two chapters of this remarkable series that cover junco diversification. They describe those subspecies and employ genetic analysis to determine how and approximately when they split apart over millennia. Captured by these chapters, you will probably want to go on to the others for they are equally interesting.

Art courtesy of Juncoproject.org

At the end of the film the many participants review the wide range of subjects that are being explored through working with juncos: how birds live in an urban environment, speciation, adaptation, climate change, the brain, hybridization, violence, how genes affect behavior, reproduction, mate choice, evolution, gene expression, range expansion, communication, maternal care, geographic variation, hormones, gonads, monogamy, sex, food, death, yourself, sensory systems, prey selection, disease ecology, olfaction, and beauty in nature. You will not come away from viewing these films without gaining a great deal of respect for these little gray birds.

The Friends of Iroquois National Wildlife Refuge directly support many of the birding programs managed at the refuge, including the cavity nesting bird program, providing bird food for the feeders at the Visitor Center, and the many birding programs offered through Iroquois Observations (Eagle Watch, Owl Prowl, etc). If you enjoy our birding programs, please consider supporting us by becoming a member (click here!) or donating (click here!).